Don't worry if you're not familiar with this animal yet. They're microscopic, so not easily observed without special equipment. But they're fascinating, so I'm sure you'll want to learn more about them soon!

Thanks to Emily, we had our first chance to photograph and film an atlantid heteropod (Atlanta sp.) that was caught in a plankton tow off Bodega Head on 17 September 2014.

Heteropods

are pelagic snails. They spend their entire lives floating and

swimming in the open ocean. You can see several adaptations to a

planktonic existence —

a

mostly transparent body and shell, a foot that's been modified into a

swimming fin, large eyes, and a radula (basically a tongue) with sharp teeth for grasping and tearing prey. Heteropods are active,

visual predators. [Facts from Roger Seapy's excellent introduction to heteropods on the Tree of Life web page.]

Here's the video. [This is pretty special, as we can't seem to locate many heteropod videos on the Internet.]

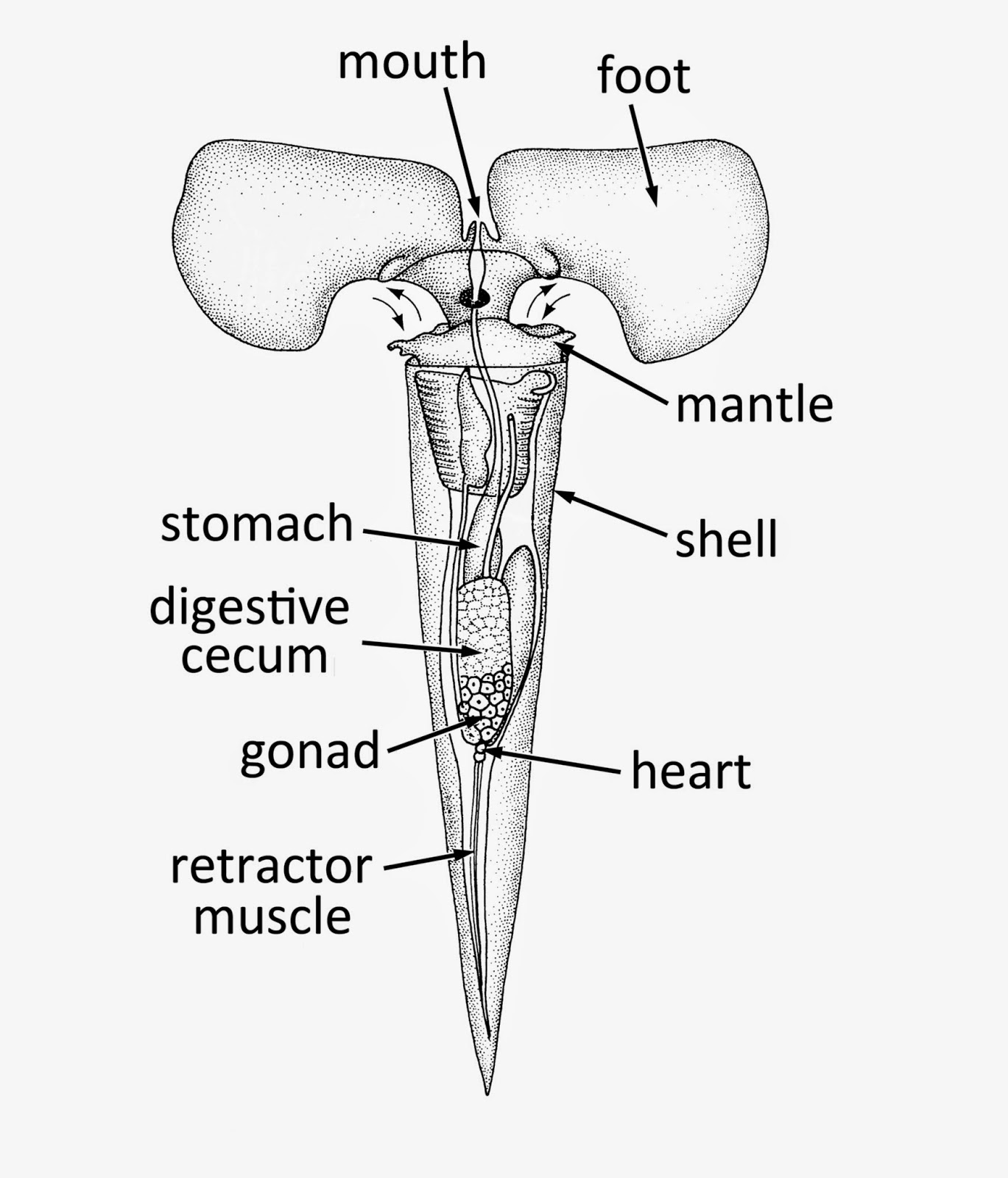

The diagram below illustrates the main body parts visible in these pictures and the video.

Modified from The Light and Smith Manual (2007)

Note the coiled shell with the unusual keel that extends from the edge of the outermost whorl. The keel apparently helps stabilize the animal as it swims with back-and-forth undulations of the swimming fin.

The animal can withdraw completely into its shell. When it does, it can close the aperture (opening) of the shell with its operculum, just like many intertidal snails that you're probably familiar with.

The fin sucker is used to secure prey, e.g., other pelagic gastropods.

The proboscis is extensible, like an elephant's trunk. It's transparent, so you can see the radula inside — the radula looks a bit like a small zipper.

The eyes are large and dramatic. Atlantid heteropods are known for interesting eye-scanning movements, which you saw in the video. Look for the rounded lens (it looks silvery). It's thought that the eyes can pick up reflected light off stationary objects.

Here's another picture to look for all of these structures:

This heteropod was swimming, so it was difficult to photograph. Below, look for the keel at the lower edge of the shell. The gill is also visible inside the largest shell whorl.

Although many atlantid heteropods are pictured as I've shown them in the first two images, their normal swimming position is with the swimming fin held up towards the surface. So it's helpful to think about them like this:

P.S. If you need an explanation of the video: There are a few different things going on. It starts with an overview of the entire animal. The eye-scanning behavior will be obvious. A close-up reveals the radula moving inside the proboscis. Then you'll see the gill and a close-up of the heart pumping. (Amazing!) After that, the heteropod extends its proboscis and its tentacles, then swims away. The video ends with a few more images to help you appreciate this little-known animal.

P.P.S. Most atlantid heteropods are found in tropical and subtropical latitudes. One species, Atlanta californiensis, is found along the West Coast up to British Columbia. The Light and Smith Manual (2007) says that Atlanta californiensis is abundant is southern California, but we're not certain how common it is in northern California. We're trying to get help identifying this individual to find out which species it is.